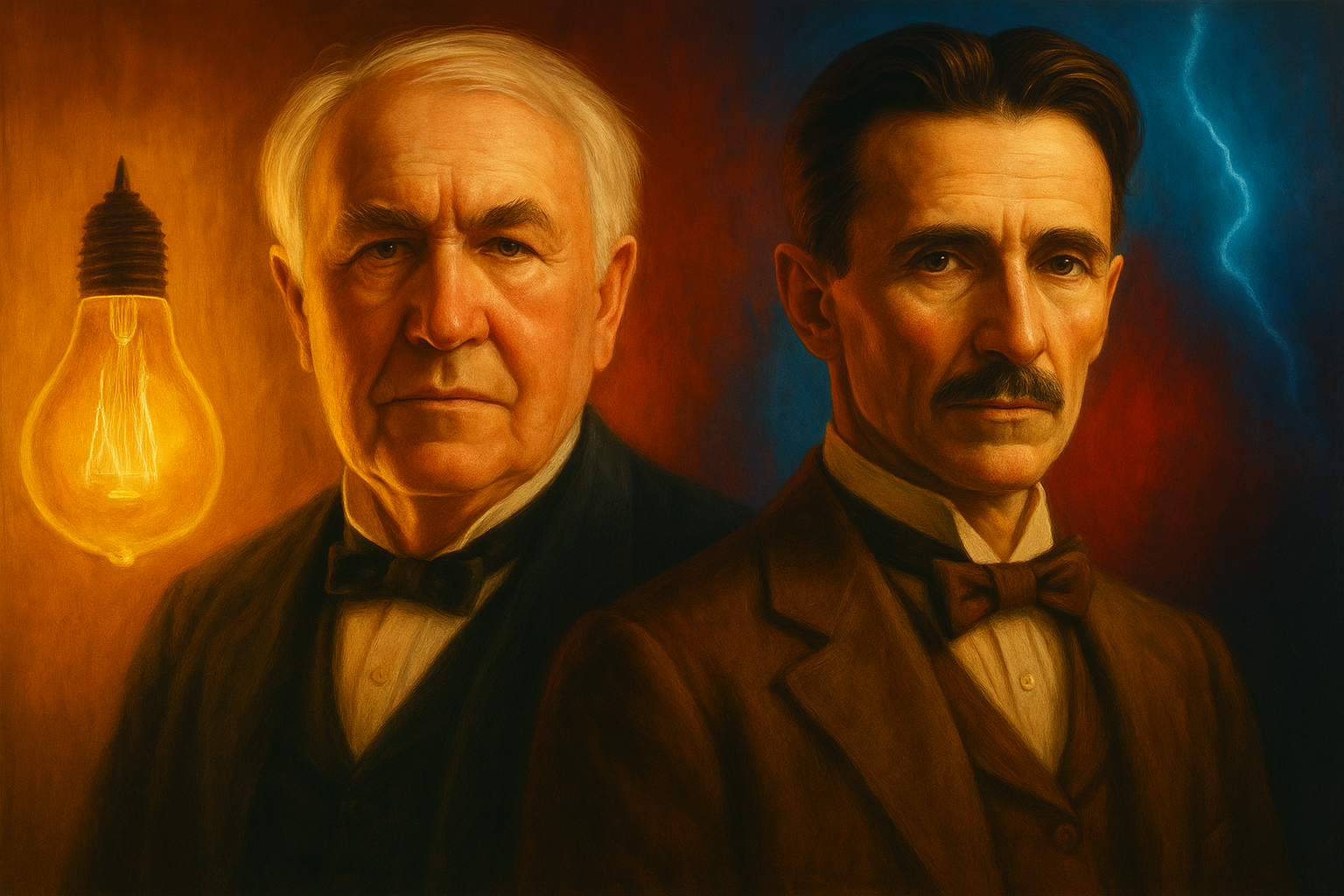

The rivalry that proved a brilliant idea means little without the business to back it.

Tesla and Edison’s rivalry has always stood out to me— both for its historical significance and for what it reveals about the nature of success. It’s a perfect case study of what separates raw talent from real-world impact.

Tesla had the better ideas. Edison had the better strategy. Tesla was the visionary. Edison was the businessman. And in the end, Edison came out on top—not because he was smarter, but because he knew how to position his ideas in a way people could understand.

Today, we celebrate Tesla—his name powers one of the world’s most iconic car brands. But during his lifetime, he was overlooked. He had world-changing ideas, but no plan to promote them.

And that made all the difference.

Brilliant Ideas, Limited Strategy

Nikola Tesla helped shape the modern world with foundational work in alternating current, wireless transmission, and early radio technology. He foresaw the vast potential of electricity long before the infrastructure existed to support it.

While he was unmatched in terms of his intellect throughout his career he often struggled with gaining funding and long-term strategy.

Tesla was often too idealistic in business—generous in negotiations and less focused on building the systems needed to scale his innovations. His ideas were revolutionary, but without the infrastructure to support them, many of them were left unrealized.

A Deal That Changed Everything

Early in his career, Tesla worked for Edison. Edison promised him $50,000 to fix a major flaw in his electrical system. Tesla delivered.

But when he asked for the payment, Edison laughed and said, “You don’t understand our American humor.”

That moment revealed the core difference between them.

Edison treated invention like business—every idea was a transaction, every promise part of a negotiation. He was sharp, strategic, and knew how to play the game.

Tesla was brilliant but naive. He lacked the street smarts Edison had—and that deal exposed it.

It marked the start of their falling out, and the beginning of a much deeper divide—between commerce and genius.

Edison the Entrepreneur

Edison combined the mind of an inventor with the drive of an entrepreneur. He surrounded himself with teams, secured funding from investors like J.P. Morgan, and turned his Menlo Park lab into a machine for industrial innovation.

He didn’t try to do everything himself. He delegated and led like a founder. Edison understood that ideas need infrastructure. His team would go on to secure over 1000 patents.

Tesla, meanwhile, worked alone. He chased breakthroughs, but often without a strategy or a team to help him scale them. Many of his inventions never left the lab.

The War of the Currents

Their rivalry came to a head during the War of Currents—a battle over how electricity would power the world. Tesla championed alternating current (AC); Edison pushed direct current (DC).

AC was cheaper, more efficient, and could travel long distances. DC was costly and limited. But Edison wouldn’t back down. He had too much to lose—and he was willing to fight dirty.

The First Smear Campaign

Edison decided to launch the first ever smear campaign. It wasn’t about science—it was about business. He saw Tesla’s system as a threat to his own, so he set out to make the public fear it.

Through gruesome demonstrations and public stunts—like electrocuting animals and supporting the use of the electric chair, Edison linked Tesla’s technology to death, branding it as unsafe for public use.

It was calculated and manipulative. But it worked. People began to associate Tesla’s ideas with risk, even though they were more efficient and advanced.

This wasn’t a fight over which system was better. It was a fight over perception. And Edison understood that in business, winning hearts often matters more than winning minds.

The Royalty That Could Have Made Tesla a Fortune

In the late 1880s, Nikola Tesla licensed his AC patents to George Westinghouse in a deal that included royalties — reportedly $2.50 for every horsepower of electricity sold. Had the agreement remained in place, it could have made him one of the wealthiest men of his era.

However, when Westinghouse Electric faced financial strain in the early 1890s, Tesla voluntarily waived his royalties to ease the burden. In doing so, he gave up the one income stream that could have turned his vision into a lasting legacy.

It was a generous act — and a costly one. The decision reflected Tesla’s idealism, but also a lifelong blind spot: he never learned to protect the commercial value of his ideas. He died in relative poverty in 1943, brilliant but broke.

Takeaways

Marketing Isn’t Optional

For a long time, I thought marketing came at the end—after the product was ready. Now my views have changed.

Marketing is how ideas spread. Its role is to generate excitement — but just as importantly, to provide clarity. It helps people understand what you’ve built and why it matters. Without it, even the best ideas can disappear.

Edison knew the game. Invention was just half the battle — the rest was knowing how to sell. Through strong networks and public appeal, he understood what marketing truly is: turning ideas into impact.

Tesla thought hard work and revolutionary ideas would be enough. But truth doesn’t always rise to the top.

That’s why one man died forgotten—and the other became a symbol of innovation. Tesla had genius. Edison had distribution. And in the end, commerce beat genius.

The Best Idea Doesn’t Always Win

Tesla’s ideas were decades ahead of their time. He imagined wireless energy transmission and developed the Tesla coil, which laid the groundwork for modern radio and remote control technology. He foresaw renewable energy systems and envisioned technology that wouldn’t become viable for another century.

But he never packaged those ideas in ways people could support or invest in. He spoke in abstract visions, not actionable plans. As a result, the world passed him by.

Edison wasn’t always the more innovative mind—but he was the better communicator. He gave the public simple stories and practical solutions. He made complex technology feel familiar. Tesla imagined the future. Edison commercialized it.

Dream Like Tesla. Sell Like Edison.

Tesla’s story is a powerful reminder: invention alone isn’t enough. Ideas don’t sell themselves.

Edison, for all his flaws, understood this. He created systems, formed partnerships, and turned ideas into commercial enterprises. That’s the power of commerce. It’s not just about profit—it’s about practicality and the ability to scale. It brings ideas out of isolation and into the real world.

Genius, on its own, is often solitary. Visionaries like Tesla tend to do their best work alone, however without support or collaboration, even the most brilliant ideas can fade into obscurity.

That’s why I always remind myself: it’s not enough to have a great idea, you need to surround yourself with the right people and processes to help it grow.

So yes—dream like Tesla.

But don’t forget to sell like Edison.

Genius inspires us. But commerce builds the future.